People-Pleasing, Trauma, and the Search for Belonging

A Healing Reflections Essay by Martyn Blacklock

(10–12 minutes)

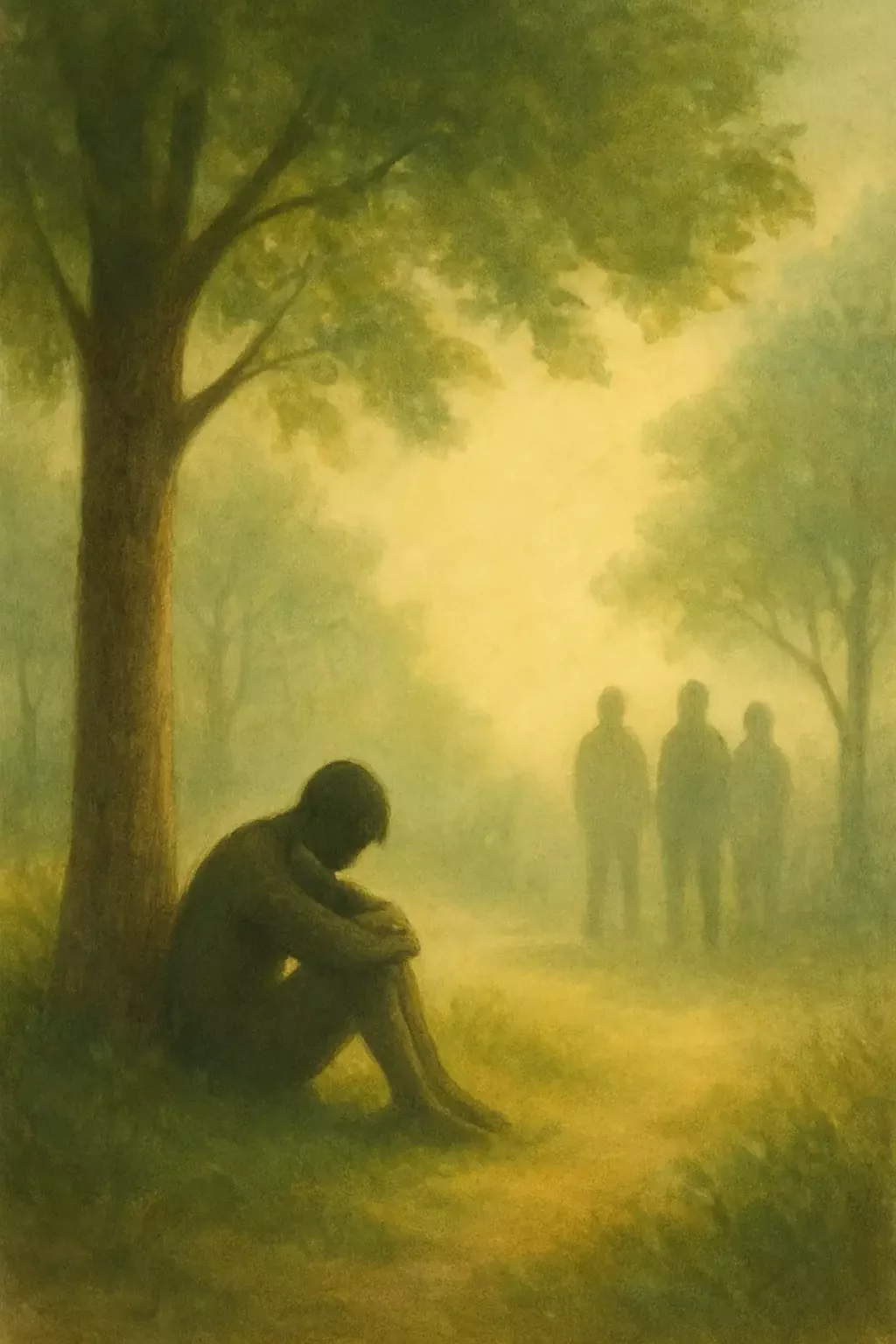

1. Introduction: When “Being Good” Becomes a Disappearance

People-pleasing is often misunderstood as a harmless trait — a sign of kindness, generosity, or natural empathy. Yet beneath its gentle surface, it frequently reflects something far deeper and more painful: the belief that authenticity is unsafe. As Elizabeth Gilbert has said, “People-pleasing is not about being good, it’s about being safe.” It is a subtle strategy of nervous-system management — a learned instinct to shape-shift so that conflict is avoided, relationships are preserved, and the fragile illusion of harmony is maintained.

But people-pleasing is not connection.

It is performance.

And performance is the opposite of belonging.

Brené Brown articulates this distinction clearly:

“Fitting in is the opposite of belonging. Fitting in is about assessing a situation and becoming who you need to be to be accepted. Belonging is about being accepted for who you are.”

People-pleasing is the art of fitting in.

Healing is the slow return to belonging.

This essay explores people-pleasing as a trauma response, a cultural inheritance, a neurospicy survival pattern, and a relational dynamic — while also offering reflections from my own life, therapeutic practice, and leadership. Most importantly, it examines how we move from fitting in, which demands self-abandonment, toward belonging, which requires truth.

2. Cultural Foundations: “Don’t Talk. Don’t Share. Don’t Feel.”

Elizabeth Gilbert often names the emotional ethos of Anglo-Saxon, Catholic-influenced households as governed by three implicit rules:

“Don’t talk. Don’t share. Don’t feel.”

These rules do not need to be spoken to be obeyed; they live in tone, silence, tension, and expectation. They train children to believe that emotional expression is inconvenient, personal truth is burdensome, and conflict is dangerous. Instead of developing an internal sense of worthiness, children learn to become what others need.

This is the birthplace of people-pleasing.

It is also the birthplace of fitting in — the behavioural contortion required to be acceptable. Gilbert calls this the “goodness script,” where the highest moral achievement is to be undemanding, silent, agreeable, and helpful.

But as Brené Brown reminds us:

“When we sacrifice who we are for the sake of belonging, we don’t actually belong — we fit in. And fitting in is hollow.”

People-pleasers inherit this hollowness.

It becomes a defining emotional atmosphere:

connection without closeness, love without safety, presence without visibility.

3. Trauma and the Fawn Response: Appeasement as Survival

In trauma theory, people-pleasing corresponds closely to the fawn response — the instinct to placate perceived threat through appeasement. When children grow up in environments defined by emotional unpredictability, criticism, shame, or unspoken rules, their nervous systems often conclude:

“If I make myself small, I’ll be safe.”

“If I keep everyone happy, I won’t be hurt.”

“If I anticipate needs, I won’t be abandoned.”

Bessel van der Kolk writes in The Body Keeps the Score that trauma is encoded not in memory but in pattern. The body learns to react before the mind can think.

People-pleasing is one such pattern.

It is the memory of danger, expressed through compliance.

The tragedy is that the strategy works in childhood — it protects connection when connection is fragile. But in adulthood, it becomes a barrier to intimacy. When appeasement becomes instinct, authenticity becomes threat.

4. Fitting In vs Belonging: The Heart of the Wound

This essay’s central spine lies in a simple truth articulated by Brené Brown:

“True belonging never requires you to change who you are. It only requires you to be who you are.”

People-pleasing is the opposite of this. It is the repeated self-abandonment that allows us to survive environments where being ourselves felt dangerous or unwelcome. This is why people-pleasers often say things like:

“I don’t know what I want.”

“I don’t know who I am in relationships.”

“I lose myself in other people.”

Because fitting in requires us to amputate the parts of ourselves that don’t align with the expectations around us.

Belonging, however, is the slow return of those parts — the parts we muted, edited, or hid. Belonging is the practice of making ourselves visible again.

5. The Neurospicy Experience: Masking as People-Pleasing

For neurospicy individuals — ADHD, autism, AuDHD, or those resonating with traits previously described as Asperger’s — people-pleasing often merges with masking. Devon Price describes masking as “the constant pressure to perform a socially acceptable version of oneself.”

Masking might include:

rehearsing responses

mimicking tone or body language

suppressing stimming

monitoring perceived “weirdness”

hiding sensory overwhelm

adjusting pace, intensity or focus

softening truth to avoid rejection

Masking is people-pleasing in high definition — a relentless attempt to fit in. But fitting in is neurologically and emotionally expensive.

Luke Beardon writes that the autistic experience is often defined by “the trauma of constant misunderstanding.” Masking attempts to solve this misunderstanding by becoming more palatable — but at the cost of selfhood, energy, authenticity, and even mental health.

Unmasking, then, becomes a return to belonging — the belonging we never experienced through fitting in.

6. Boundaries and the Return to Self

Nicole LePera describes self-boundaries as the first stage of healing from people-pleasing. These boundaries are internal commitments such as:

“I will pause before agreeing.”

“I will not abandon myself to regulate others.”

“I will trust my discomfort as information.”

“I will honour what is true for me.”

Sparrow’s Nest Counseling calls this “re-introducing yourself to yourself.”

Boundaries with others then become possible — boundaries that are not punishments, but invitations to real connection. I often use the definition:

“A boundary is the space in which I can love you and me equally.”

People-pleasers often fear that boundaries will cause loss.

In reality, boundaries prevent self-loss.

They create belonging — authentic, mutual, sustainable belonging — rather than fragile fitting in.

7. My Own History: People-Pleasing in Leadership, Community, and Therapy

My understanding of people-pleasing has been shaped through lived experience, not theory. In my time managing at HSBC, my instinct was always to accommodate, soothe, and absorb emotional tension within the team. This led to burnout, imbalance, and a lack of accountability. A manager once told me I needed to “show my teeth” — not aggression, but clarity. This became a turning point in my understanding of leadership and truth.

In Healing Together, I have found myself softening our carefully structured boundaries — refund policies, booking requirements, community agreements — because I feared disappointing individuals. This created logistical complications and emotional imbalance. When I honour our boundaries, the whole community benefits. Fairness increases. Trust grows. And those misusing my people-pleasing tend to fall away.

In therapy, people-pleasing is an ethical risk. My aim is warmth, attunement, and relational depth — not blind agreement. As a counsellor, I must hold truth as tightly as compassion. My clients do not need a version of me that fits in; they need a version of me that helps them belong to themselves.

8. Intergenerational Silence: The Inherited Cost of Fitting In

People-pleasing often stems from intergenerational trauma.

A family that prized silence creates children who prize invisibility.

A family that feared anger creates adults who fear conflict.

A family that rewarded compliance creates adults who equate safety with self-abandonment.

Brené Brown writes: “We can only belong if we stop hustling for worthiness.”

People-pleasing is a form of hustling — a generational ritual of earning love rather than receiving it. When we begin to break this pattern, we are not only healing ourselves; we are interrupting a lineage.

9. The Practice of Unlearning: From Fitting In to Belonging

Healing from people-pleasing involves:

pausing before responding

noticing the urge to appease

naming small truths

tolerating disappointment

regulating the nervous system

learning conflict as connection

reconnecting with desire

welcoming anger as information

listening to the inner child

Jeff Foster writes:

“What you long for is deep intimacy with your own experience.”

But intimacy with our experience requires visibility — and people-pleasing makes us invisible.

To heal from people-pleasing is to become visible again.

It is to choose belonging over fitting in.

Truth over performance.

Love over fear.

10. Conclusion: The Courage to Belong

People-pleasing is a survival strategy — a way of fitting in.

Belonging is the antidote — a way of being fully alive.

Brené Brown’s words echo through the heart of this essay:

“You only belong when you can be yourself. Fitting in requires you to be something you’re not.”

To stop people-pleasing is to risk the discomfort of authenticity.

To risk boundaries.

To risk truth.

To risk visibility.

But it is also to risk connection — real connection — the kind that sustains us.

Healing from people-pleasing is an act of love.

And belonging is the home we return to.

Further Reading

Brené Brown

Brown, B. Daring Greatly (2012).

Brown, B. Braving the Wilderness (2017).

Brown’s work underpins the belonging vs fitting in framework, and the courage of vulnerability.

Elizabeth Gilbert

Gilbert, E.

Relevant talks, interviews, and essays on people-pleasing, emotional inheritance, and cultural conditioning.

Bessel van der Kolk

Van der Kolk, B. The Body Keeps the Score (2014).

Grounds the discussion of trauma patterns and the fawn response.

Devon Price

Price, D. Unmasking Autism (2022).

Explores masking, neurodiversity, and the emotional cost of fitting in.

Luke Beardon

Beardon, L. Autism and Asperger Syndrome in Adults (2022).

Informs sections on autistic experience, misunderstanding, and masking.

Nicole LePera

LePera, N. How to Do the Work (2021).

Provides the framework for self-boundaries and trauma-informed healing.

Cloud & Townsend

Cloud, H., & Townsend, J. Boundaries (1992).

Classic text on relational boundaries and identity protection.

Jeff Foster

Foster, J. The Way of Rest (2016).

Offers philosophical grounding to authenticity and intimacy with experience.

Sparrow’s Nest Counseling

“7 Steps to Set Boundaries With Yourself.”

Used for conceptualising self-boundaries and identity restoration.