How Mis-Seen Wounds, Neurospiciness, and Childhood Echoes Shape Our Most Repeated Fights.

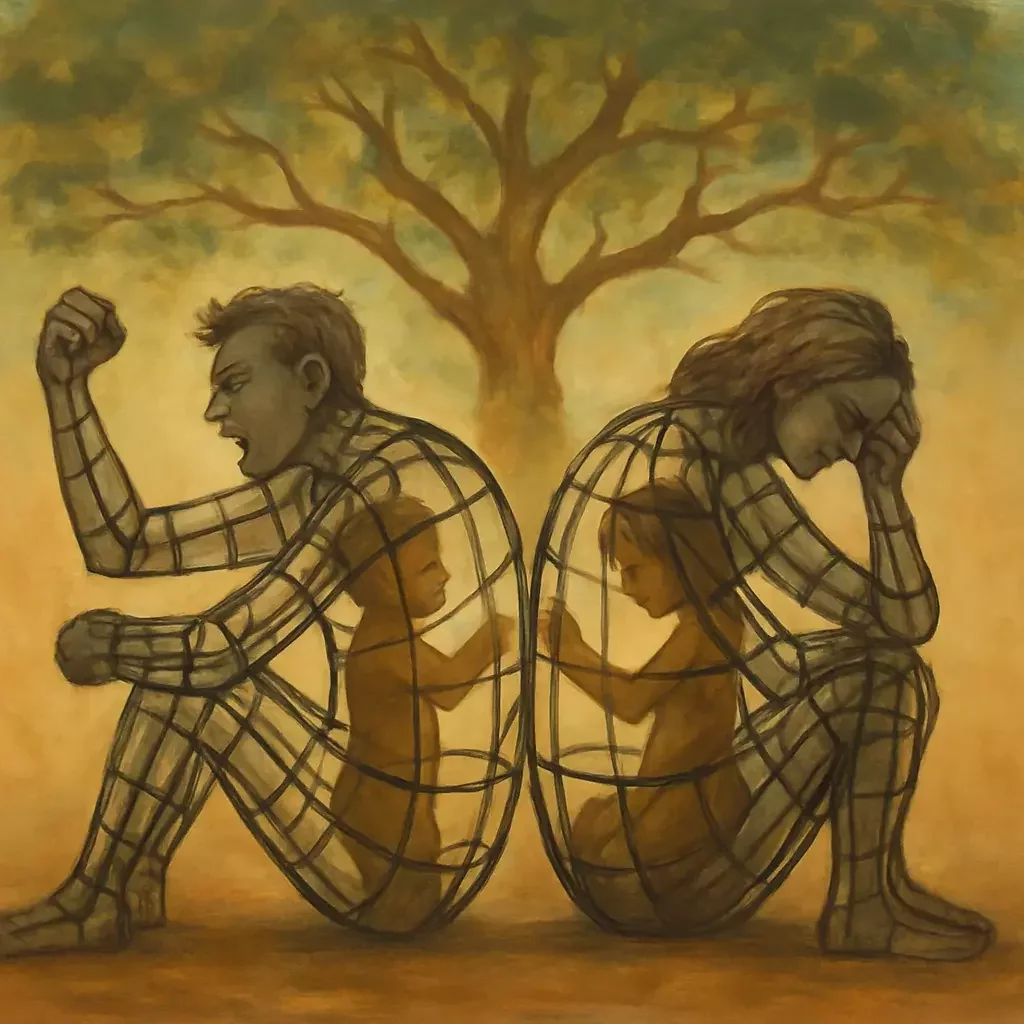

Every couple has a version of the “fight that keeps returning.” It might start with a small misunderstanding, a tone, a difference of perspective, or a moment where one partner’s meaning doesn’t land as intended. What begins as a normal conversational mismatch suddenly escalates into defensiveness, frustration, or emotional withdrawal. Many couples look back afterwards and ask, “How did that get so big, so fast?”

Oprah Winfrey once said that beneath all human communication lie three questions:

“Do you see me? Do you hear me? Does what I say mean anything to you?”

These questions form the emotional foundation of attachment, belonging, and relational safety. When the answer feels like “no,” even momentarily, the nervous system reacts — often dramatically — because mis-seeing is not just a misunderstanding. It is an identity wound.

This essay explores why these moments feel so intensely destabilising, how neurospiciness can amplify the experience of being mis-seen, and why the path forward is not better communication techniques but the deeper, ongoing practice of healing together.

1. A Personal Example: The Wound of Being Mis-Seen

In my relationship with Amram, there is one recurring trigger that can rapidly activate both our nervous systems: the sense — real or perceived — that the other thinks we are “stupid,” “missing something obvious,” or “not understanding.” Interestingly, this is never about intelligence. It is about identity, respect, and the longing to be accurately seen. What ignites the conflict is not the content of the disagreement but the painful feeling of being misrepresented.

Relational neuroscience explains this vividly. Stephen Porges, in his Polyvagal Theory, argues that our nervous system is constantly scanning for cues of safety or danger. Misattunement — when someone close to us perceives us inaccurately — is registered by the body as a threat to belonging (Porges, 2011). Because belonging is foundational for survival, especially in childhood, the adult body reacts with surprising intensity.

When one of us feels seen wrongly, old neural pathways fire instantly. The body recognises the feeling long before the mind does. The conflict is no longer happening in the present; it is occurring in the residues of the past.

2. My Pattern: Niceness as a Survival Strategy

Growing up, anger was not modelled safely for me. It was unpredictable in others and discouraged in me. The implicit message I absorbed was that speaking difficult truths, expressing discomfort, or challenging someone’s behaviour was “not nice” and therefore unsafe. As Gabor Maté (2019) describes, children routinely sacrifice authenticity in favour of attachment, because maintaining connection is biologically essential.

So I became “nice” — agreeable, cheerful, compliant. Anger was forbidden, even to myself.

My nervous system internalised the belief that safety comes from being good, pleasant, easy, and never causing trouble. When conflict arises now, especially when I feel mis-seen, the old survival strategy resurfaces. I firstly go to minimise, placate, retreat, or deny that I am upset, even as my body registers the threat. What looks like calm on the outside is often fear on the inside. It has changed through many years of practice, but I still carry this initial reaction in the most triggering moments.

3. Amram’s Pattern: Sensitivity, Precision, and Ancestral Fire

Amram’s pattern is different, shaped by his sensitivity, his perceptual clarity, and the transgenerational trauma carried by his family. His grandmother was a WW2 refugee, and that legacy of vigilance, justice, and survival lives in him.

When he feels mis-seen, especially as incompetent or foolish, the intensity of his reaction is immediate and honest. It is not aggression. It is clarity. His anger is a boundary, not a weapon — an insistence on truth rather than an attempt at harm.

Where I hide anger, he does not. Where I soften, he sharpens. Where I placate, he confronts.

Our nervous systems move in opposite directions, each protecting an inner child who learned different lessons about what safety required.

4. Our Neurospiciness: A Double-Edged Mirror

Neurospiciness intensifies both misunderstanding and connection.

I was diagnosed with ADHD, though the more I understand myself, the more the AuDHD or autistic profile resonates. Research on ADHD and autism shows overlapping traits such as:

- heightened sensitivity to rejection and mis-seeing

- emotional intensity

- difficulty masking under relational stress

- deeply intuitive pattern recognition

- sensory-based overwhelm

- difficulty shifting out of defensive states

- rapid nervous system activation(Hendrickx, 2015; Price, 2022)Amram exhibits traits associated with what was once referred to as Asperger’s and is now understood within the autism spectrum. The literature describes this profile as including:

- a direct, literal communication style

- heightened sensitivity to inconsistency or misrepresentation

- strong justice-oriented responses

- intense perceptual detail

- difficulty masking emotional truth

- a low tolerance for emotional dishonesty or distortion

(Tony Attwood, 2007; Milton, 2012; Vermeulen, 2015)

But this difference also creates a form of love that is unusually honest. Neurospicy relationships often excel in intensity, authenticity, and depth. As Devon Price notes, autistic connection is “direct, intuitive, and intensely sincere” (2022). When we get each other, we get each other at a level that feels rare and profoundly grounding.

And when we don’t — the rupture burns brightly.

5. Why Mis-Seen Hurts So Much: The Shame Response

When one partner mis-sees the other, the emotional pain often comes not from the perceived insult but from the resurgence of shame. Brené Brown distinguishes:

- Guilt: “I did something bad.”

- Shame: “I am bad.”

Shame attacks identity. Mis-seeing feels like misjudgement. Misjudgement feels like shame. And shame triggers anger.

Anger, in this context, is not the primary emotion. It is the shield protecting the wounded self. As Brown writes, “Anger is a bodyguard for the most tender part of our hearts” (2012). When either of us feels misrepresented, anger rises to cover the vulnerability. The fight is not about content. It is about self-protection.

6. Defensive States Are Not Personality Flaws — They Are Implicit Memories

It is common for couples to interpret intense reactivity as irrationality, immaturity, or lack of control. But research into complex trauma suggests the opposite. Janina Fisher (2017) describes many defensive states as “implicit memory intrusions,” meaning the body reacts in ways that once ensured survival.

- Hypervigilance was once necessary.

- Shutdown once protected from overwhelm.

- People-pleasing once preserved attachment.

- Anger once kept danger at bay.

These states are not pathological. They are logical. When a partner’s tone, wording, or reaction resembles something formerly threatening, the body responds as though the threat is happening again. Van der Kolk’s well-known phrase captures this precisely: “The body keeps the score” (2014). Thus, relational conflict often reveals not incompatibility but unhealed memory.

7. Co-Regulation: The Real Work of Relationship

Most couples believe communication is the core of relational harmony. Yet the evidence suggests something far more biological: relationship is about nervous system regulation. Deb Dana, drawing from polyvagal research, writes that “humans are not designed to self-regulate; we are designed to co-regulate” (2018).

Co-regulation is the process by which two bodies:

- soothe one another

- downshift from threat to safety

- offer grounding through presence

- reduce defensive arousal

- restore connection through attainment

John Gottman’s research adds that couples do not fail because of conflict but because of poor repair. The repair process is the heart of relational longevity. When we repair through warmth, attunement, accountability, and clarity, conflict becomes a pathway to deeper intimacy rather than a sign of incompatibility.

8. Love Is a Practice of Healing Together

This is where the personal and the universal meet. My relationship with Amram is not smooth or serene — it is alive, honest, and healing. Our differences do not prevent connection; they create the conditions for relational growth. Through our conflicts, we learn how to honour:

- each other’s inner children

- each other’s nervous systems

- each other’s sensory worlds

- each other’s perception of truth

- each other’s trauma histories

- each other’s neurotype

- each other’s longing to be seen accurately

Healing has not been the absence of conflict. It has been the transformation of conflict into understanding. And it is from this lived experience that our community work emerges. Healing Together is not an abstract idea; it is the landscape of our relationship — our shared commitment to learning how to love each other better so we can help others do the same.

9. Jeff Foster: Meeting Ourselves Through Another

Jeff Foster writes:

“What you long for is intimacy with your own experience…

And that cannot come from outside yourself.”

There is truth in that. But relational neuroscience adds an essential nuance: before we can meet ourselves, we often need someone else to be with us first. Co-regulation precedes self-regulation; sometimes we didn't get this in childhood and the need continues into adulthood. Safety in the other precedes safety in the self.

Perhaps this is what our most intimate relationships are for:

- to hold a mirror steady

- to help us see ourselves clearly

- to give us a safe place to experience the feelings once too overwhelming to face alone

Love becomes the bridge between the body that survived and the self that wishes to live more fully.

10. Conclusion: What We Are Really Fighting For

When couples keep having the same argument, it is rarely because they cannot communicate. It is because their inner children are asking the same unanswered question:

“Do you see me?

Do you hear me?

Do I matter to you?”

Conflict dissolves when these questions receive a sincere yes. And that yes is not given once — it is given repeatedly through the daily practice of relational healing. Love, at its heart, is a practice of healing together.

Two people learning to feel safe in each other’s presence. Two nervous systems learning to settle. Two histories learning to co-exist. Two inner children learning that this time, they are not alone.

This is what allows a relationship not just to survive but to become a place of transformation — where both people grow not away from each other, but toward the selves they were always meant to become.

Further Reading & Sources

Attwood, T. (2007). The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Brown, B. (2012). Daring Greatly. Avery.

Dana, D. (2018). The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy. Norton.

Fisher, J. (2017). Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors. Routledge.

Gottman, J., & Gottman, J. (2015). 10 Principles for Doing Effective Couples Therapy. Routledge.

Hendrickx, S. (2015). Women and Girls with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Maté, G. (2019). The Myth of Normal. Penguin Random House.

Milton, D. (2012). “On the ontological status of autism: the ‘double empathy problem’.” Disability & Society, 27(6).

Porges, S. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory. Norton.

Price, D. (2022). Unmasking Autism. Harmony.

Van der Kolk, B. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score. Viking.

Vermeulen, P. (2015). Autism as Context Blindness. AAPC Publishing.

Winfrey, O., & Perry, B. (2021). What Happened to You? Bluebird.

About the Author

Martyn Blacklock is a counsellor, yoga teacher, and retreat facilitator who weaves psychology, embodiment, and nature connection to support people in rediscovering wholeness. He is the founder of Healing Together, a growing community dedicated to compassionate, integrated healing.